One of the most common things I see today on social media is questions about what is eating my plant. Insect pests are part of the biodiverse landscape we live in. Without most of them, we would not have a healthy landscape. Birds, mammals, and many other parts of the ecosystem rely on a diet that includes many insects.

What I aim to discuss here, are the invasive and native insect pests that we want to limit the population of, or eradicate completely. While there are a broad range of insects affecting many hundreds of species of trees; I will focus in on those affecting trees in the Central Great Plains and Midwest areas.

I have already written several detailed blogs on some insects. Re-discussing these insects would be redundant, so I will just mention them now: Aphids, Kermes Scale, and Japanese Beetles. You can click on the links to get to those blogs.

Native Insect Pests of Trees

I refer to these as native pests, because they are from North America and pose only a small threat to trees. However, if left alone in great numbers, where predator populations have been reduced, they can decimate monoculture plantings of trees (windbreaks, etc.).

Bagworms

There are few homeowners in my part of the United States who do not know what bagworms are. I have seen and destroyed millions of bagworms through my tenure at Grimm’s Gardens and previous companies.

Technically, bagworms are not “worms”, but rather a moth caterpillar that uses a shredded leaf bag to protect itself from predators. These caterpillars build the bag around them as they feed and grow. They use a combination of silk and leaves to make this tough bag. If you have ever tried to split one open, you will know how strong it is.

Life Cycle

Starting in May, bagworms begin to hatch. They hatch over a 6 to 8 week period. Newly hatched caterpillars with bags are 1/8 inch long and difficult to spot on trees.

The caterpillars feed for 6 to 10 weeks, until they reach maturity. Then, the males pupate into moths and visit the females, which do not change into moths. The females then lay up to 1000 eggs in the bag, and she drops out to the ground to die.

What do They Eat?

Bagworms are known for their severe damage to windbreaks, especially those of arborvitae, Eastern red cedar, and spruce. However, they are not limited to evergreens, and can be found on almost anything. When there are increased numbers of eggs laid, due to lack of predators, bagworms feed on deciduous trees, shrubs, even perennials!

I have observed bagworms crawling across and feeding on lawns in between trees. In exceptionally bad years, they will also eat paint, flags, and cloth.

How do I Control Bagworms?

In the right ecosystem, bagworms do not get out of control, because natural predators keep them in check. Parasitoid wasps, yellowjackets, woodpeckers, and sapsuckers all feed on the larva or caterpillar of the bagworm.

However, when populations are too large, and tree damage is too great, chemical control is necessary. The best chemicals for killing bagworms are stomach poisons, which are ingested by the caterpillars as they feed. The following are chemicals that can be used for bagworm control.

- Bifenthrin

- Spinosad

- Bacillus thuringiensis

- Permethrin

- Cyfluthrin

NOTE: ALL CHEMICAL LABELS SHOULD BE FOLLOWED BEFORE APPLYING ANY PESTICIDES

Another method for controlling bagworms on smaller shrubs, trees, and perennials is to remove the bags by hand and thrown them into soapy water or a bonfire. Maybe you can pay your children a penny for every bag they collect.

Fall Webworm

I know you have seen them, white webbing in trees in late summer and into fall. These are not some super-spiders getting ready for the apocalypse, but rather, fall webworms. These caterpillars are a species of moth that use silken webs to protect themselves from attack.

Just like bagworms, webworms are not “worms” ate all, but caterpillars. They feed in large groups, defoliating large portions of trees, before anyone knows what is happening. For the most part, webworms feed too late in the year to cause significant damage. But their damage can be aesthetic, and is easy to control.

Life Cycle

In midsummer, around July, adult moths emerge from their cocoons and begin to lay eggs on trees, usually in the canopy. The eggs, laid in flat masses, hatch, and caterpillars feed gregariously. Their feeding gives the canopy a skeletonized look as they do not eat the leaf veins.

Caterpillars feed for several weeks, usually into mid-September, then adults crawl from the nest to the ground. Once on the ground, they make a silken cocoon and overwinter in the pupal stage. They overwinter in leaf litter, attached to buildings or trees, or in loose soil.

What do Fall Webworms Eat?

These hungry caterpillars feed on a wide range of over 100 deciduous trees. Here in Northeast Kansas, I have seen them mostly on walnut, hickory, redbud, honeylocust, and maple. But they really seem to like walnut the best around here.

How do I Control Them?

Unlike bagworms, there is usually no need to apply a chemical control on fall webworm. They rarely completely defoliate trees. When you first see a nest of webworms, cut it from the tree with pruners or loppers, and throw the whole mass into a bonfire. This is the easiest method of control.

If you are really concerned about the health of the tree or if it is already stressed from drought or other factors, you may want to use chemical controls. The best chemicals for fall webworms are the same as mentioned above for bagworms. Please follow all chemical labels before spraying.

Leaf and Twig Galls

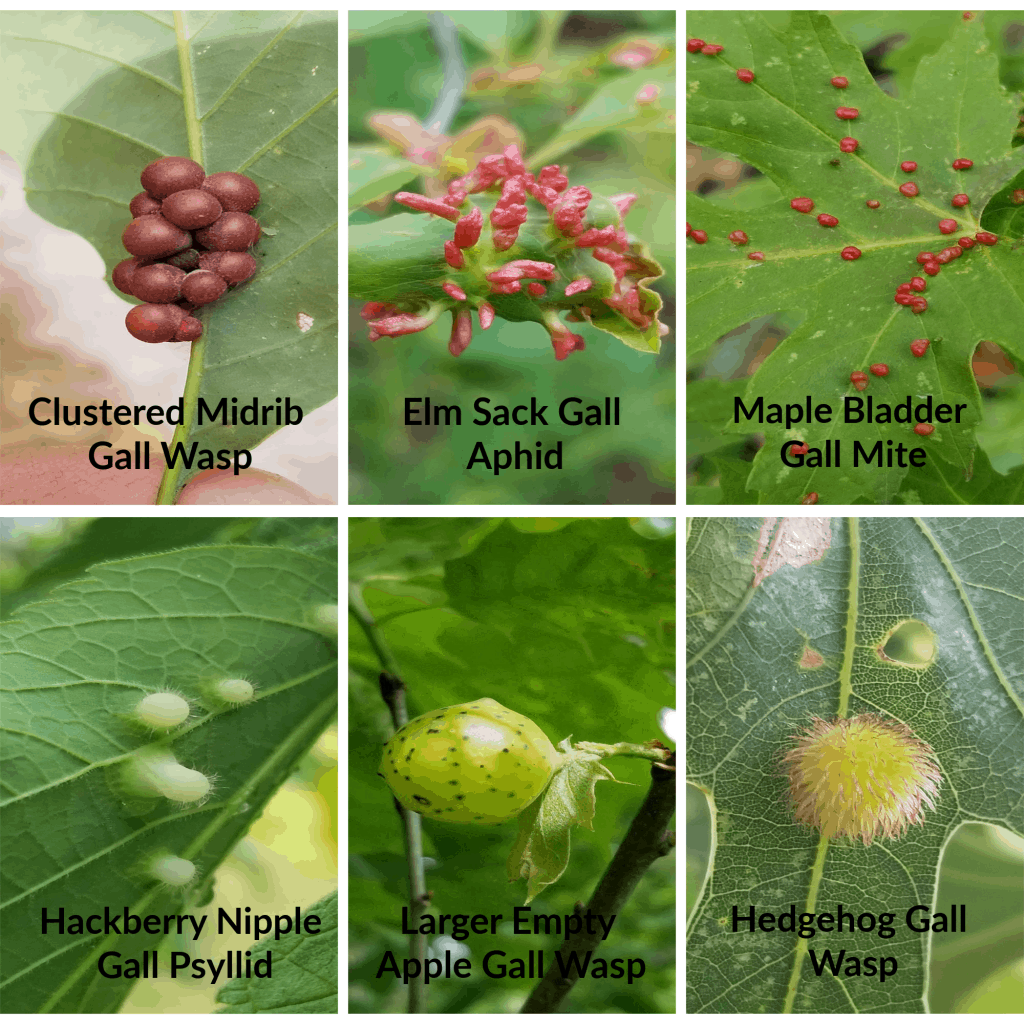

There are a large number of different gall-forming insects that affect trees. Mites, wasps, aphids, midges and others form galls on leaves and twigs when they are feeding or laying eggs. The eggs hatch inside the gall and the insects feed from the safety of the gall.

Galls are aesthetic, causing very little damage to the tree. Oak trees have a large number of galls, but they can be on nearly everything. The following photos are just a few of the many galls that can be found on trees.

Invasive Insect Pests of Trees

If only we could have kept these insect pests out of our country. I have no idea how destructive some of our native pests would be in other countries, but I can imagine. Since my knowledge centers around insect pests in the Central Great Plains and Midwest, do not look for information on the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, Asian Longhorned Beetle, or Asian Citrus Psyllid.

The insects I am going to cover are already problematic in the area that I cover. I am including links to information on the above insects, just click on each to find info.

Emerald Ash Borer

The emerald ash borer, also known as EAB, is one of the worst pests to come to the United States. Despite the fact that it only feeds on ash and fringetree, the economic impact is HUGE. There are 17 species of ash tree in the continental U.S. and Canada. And billions of trees scattered across the landscape.

Ash trees have been widely used as shade trees for their size and good fall color. Their wood is prized for furniture, baseball bats, and firewood. And there are numerous species of moth, butterfly, and other insects that will be affected if ash trees disappear from the landscape.

EAB Life Cycle

The adult EAB emerges in May to June, and lays eggs in the crevices of susceptible trees. The eggs hatch 7-10 days later and bore into the tree. They feed on the inner bark and phloem, making winding galleries that stop the flow of nutrients from the roots to crown, causing crown dieback.

In autumn, feeding diminishes and stops, and the larvae form a pupal sac inside the gallery or near the bark. They overwinter as a pupa before emerging through tiny, D-shaped exits holes as adults in May. Adults do feed lightly on bark before mating and egg-laying.

How to Control Emerald Ash Borer

There are 3 recommended treatments for EAB. These applications need to be applied to ash trees before EAB is found in area, or within 1-3 years of detection of EAB in the tree. The best method of control is as a preventative.

However, these applications will need to be done through the life of the tree, making treatment only advisable for specimen trees, shade trees that are the only source of shade, or special/memorial trees.

OPTION 1

Good: Tree & Shrub Systemic Drench Active Ingredient: Imidacloprid

Application: It is applied in the spring, and yearly for best coverage

Risks: Possible canopy dieback from EAB even if treated: 20-30%

Benefits: Low price point. Can be applied by customer.

Price: Approx. $0.20 per inch diameter to self-apply. (2016 Pricing)

Price: $2 per inch diameter to have us apply plus travel. (2016 Pricing)

OPTION 2

Better: Safari & Pentra-Bark Spray Active Ingredient: Dinotefuran

Application: Yearly by certified professional.

Risks: Possible canopy dieback from EAB even if treated: 15-20%. High risk to applicator.

Benefits: Better distribution & coverage throughout tree. Faster uptake.

Price: $7 per inch diameter per year plus travel. (2016 Pricing

OPTION 3

Best: Boxer Injection Active Ingredient: Emamectin Benzoate

Application: Every 2 years by certified professional.

Risks: Possible canopy dieback if treated is barely noticeable: 5-10%. Injection wound is minor.

Benefits: Best control. Most reliable. Fewer treatments needed (apply every other year).

Price for Trees 0-20” Diameter: $10 per inch diameter every other year plus travel. (2016 Pricing)

Price for Trees 20”+ Diameter: $12 per inch diameter every other year plus travel. (2016 Pricing)

Spotted Lanternfly

While this pretty, but very invasive pest is not yet in Kansas or close by, we are expecting it to arrive within the next 10 years. Already, many of my colleagues further east are dealing with it.

Spotted lanternfly is a planthopper, which falls into the group of insects that causes damage with piercing/sucking mouthparts. This means that when they feed, they suck plant juices, weakening and killing the plant. They are a large problem on orchards and vineyards, as well as many other native and nonnative plants.

(Photo from Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture)

This pest was first discovered in Pennsylvania in 2014 and has spread rapidly into 5 other nearby states. While spotted lanternfly is easily killed by pesticides, it is difficult to manage as they move from wild areas to cultivated areas.

Life Cycle of Spotted Lanternfly

Eggs hatch in May and June and the nymphs of spotted lanternfly begin feeding. There are 4 moltings or instars before the nymphs turn into adults. Adults mate in August and begin laying eggs in September. Adults are killed by a hard freeze, but the insect overwinters as eggs in masses on plants or other surfaces.

Controlling Spotted Lanternfly

As I said above, killing this pest is easy. it can be done with almost any chemical formulation, even soapy water sprays will kill this pest. However, the real problem is stopping its spread from quarantine zones along the east coast.

The spotted lanternfly will lay egg masses on almost any surface, and can jump short distances onto vehicles, trucks, and trains. The nymphs, like aphids, are easily attached to clothing and animals.

If you think you have spotted lanternfly, and do not live in a known quarantined area, please call your local extension office NOW.

Conclusion

While there are many insect pests out there, these that I have mentioned and referenced to are considerable pests of trees in Central Great Plains and Midwest. I will continue to monitor the spread of pests into our region and update you as more information is available.

Excellent information. Thanks for the education and grateful for photos.