Bumblebees may not be the most favorite bee of gardeners, but they are important. They are one of the first bees I see each spring (along with honeybees) and they are the largest. My kids like to ask if they can go and pet the bumblebees. And of course, I say no, because I want all bees to be left alone. But it is nice to think you could pet a bumblebee.

I grow my gardens for all insects, not just bees and bumblebees. But because of the great diversity I have, lots of bumblebees show up. And I mean lots! Each year, I follow various gardening forums, and so many people in Kansas, Nebraska, and across the country complain of declining bee and insect populations. But in my own garden, I have observed more of every species, each year. I attribute that to my lack of pesticide use, organic gardening practices, garden diversity (I collect plants), and increased use of space for flower beds and not lawns.

How can gardeners increase their biodiversity when it comes to bumblebees (and other bees)? And are the bees really declining? What can gardeners in urban areas do about the challenges facing sustainable gardening? Searching for the answer often leads me back to my own backyard; a haven for wildlife, insects, and me.

The Life Cycle of Bumblebees

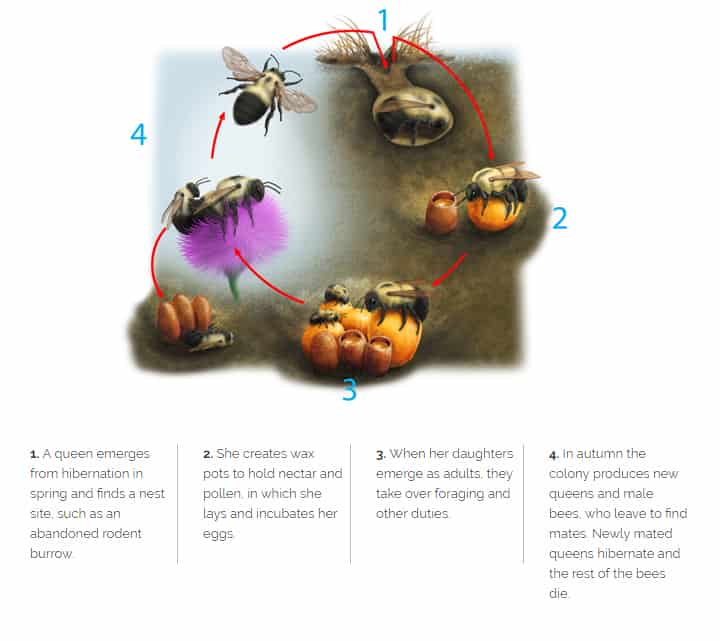

Bumblebees are the only truly native social bees of North America. They live in colonies with different casts of jobs, and have overlapping generations in the same hive, just like honeybees. But they do not produce honey, so many people do not focus on them. However, unlike the nonnative honeybee, a bumblebee hive last for one season, from spring until autumn, then restarts again in spring from 1 queen.

The single queen will create wax brood cells, then provide nectar and pollen. Then she lays eggs. These first eggs hatch in 4 to 5 weeks and will become worker bees which help tend the next generation of young in the brood cells. They also go and forage for food (pollination). As the season draws to a close, new queens and drones emerge and mate, then the new queens find overwintering sites away from the original nest. See photo below.

What do They Eat?

Bumblebees are generalist feeders. This means that they are not picky about which plants they visit. However, there are a few plants which do need bumblebee pollination, to reproduce. I have seen them out earlier than any other bee, even in warm Decembers looking for food. Usually, with the first plants of spring in March, they are there.

Plants such as potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, and melons are almost exclusively pollinated by bumblebees. Also, native monkshoods (Aconitum) and orchids need these bees to survive and proliferate. So, if you have a big vegetable garden like me, you want the pollination services provided by bumblebees.

Are Bees Really Declining?

It may be too hard to know the truth. Finding reputable research that studies a broad range of bees and other insects is difficult. There is a lot of research on honeybees, and some of the imperiled bees, but little else to help gardeners understand what is going on. Certainly, habitat loss due to farming, city enlargement, and road construction has endangered many bees, but are they really too far gone?

The research is also hard to understand. Most studies agree that bees are declining in general, with no specific rate per year. Main causes of decline are linked to habitat loss, diseases, mites, pesticides, and air pollution. There are several bees, bumblebees included, which are extinct, or are on the Endangered Species List. There 75 species of insects on the Endangered Species List for North America, and of those, 7 are bees (mostly in Hawaii), and only 2 are bumblebees. The 2 species of bumblebees are the Franklin’s (on the west coast), and the Rusty-Patched (east of the Missouri River).

Besides this, most of the articles I found agreed that the American bumblebee has declined by estimates up to 96% across the United States, and is gone from 8 states completely. But if all this is true, why has it not been put on the Endangered Species or at least Threatened Species list? Because, despite population decline, there are still a lot of bees out there. And is some areas, such as my garden, bee species are increasing.

What Can Gardeners do to Combat Declining Bee Populations?

Diversify. This is the most important thing for gardeners to do. Whether you mostly grow vegetables, or cut flowers, or do a variety of everything, planting a diverse landscape with as many species of trees, shrubs, grasses, sedges, perennials, and annuals will benefit not only bees, but all insects and pollinators.

The next most important thing to do is to reduce or completely rid your garden of pesticides. This is more difficult, as we face rising problems from Emerald ash borer, Japanese beetle, and others which are hard to combat without the use of pesticides. But options are becoming more available.

Diversifying Your Garden

If you have read many of my blogs before, you know I talk a lot about garden diversity. It is the most important factor in gaining an abundance of insects, spiders, birds, and mammals to your garden. With them also comes a variety of predatory insects, invertebrates, reptiles, birds, and mammals. I have seen bumblebees on nearly every species of flowering plant in my garden, even on trees and shrubs.

To diversify your garden, you should look to have a minimum species count for each of the following types of plants:

- Trees (5 or more genera, no more than 4 species per genus)

- Shrubs (5 or more, no more than 3 species per genus)

- Grasses and Sedges (4 or more genera, no more than 5 specie per genus)

- Perennials (10 or more, no more than 5 species per genus)

And more of your genera and species need to be native than not. You should shoot for at least 60% native to your ecoregion. For example, in my own landscape, not counting vegetables, I have 81% native trees, 73% native shrubs, and 79% native perennials and grasses. Because of this, I get more diverse each year in terms of insects, other arthropods (spiders, centipedes, etc.), reptiles, birds, and amphibians.

How to Reduce Your Need for Pesticides

Reducing the need for pesticides may be easier than you think. I have never been a proponent of pesticides, and I have gotten through a lot of gardening without most of them. Despite having a Commercial Pesticide Applicator’s license in Kansas and Nebraska, I only use it when extremely necessary.

To combat pests such as Japanese beetles, the use of traps and trap crops are extremely important. in 2022, for the first time, I put up 1 Japanese beetle trap on the edge of my yard, about 3 weeks after first hatch. I cut the bottom of the trap off, and had the caught beetles falling into a 30 gallon barrel with water. Each day I would scoop out the beetles (anywhere from 50 to 100, and feed them to my ducks. You could do something similar, but scoop them out into a tub of soapy water if you do not have ducks. Or handpick them from trap crops (Oenothera biennis is what I use) and drop them into soapy water.

Also, learning your insects, both pests and predators, will go a long way towards knowing if you even need to spray. For 99% of the pests in the garden, no treatment is required, predators will hand it. The 1% that needs attention includes EAB, pine wilt, Dutch Elm Disease, iron chlorosis, red headed flea beetle, and Japanese beetle. Of these, the first 5 can be treated with a systemic insecticide or fungicide, which limits exposure to other insects.

Planting for Bumblebees

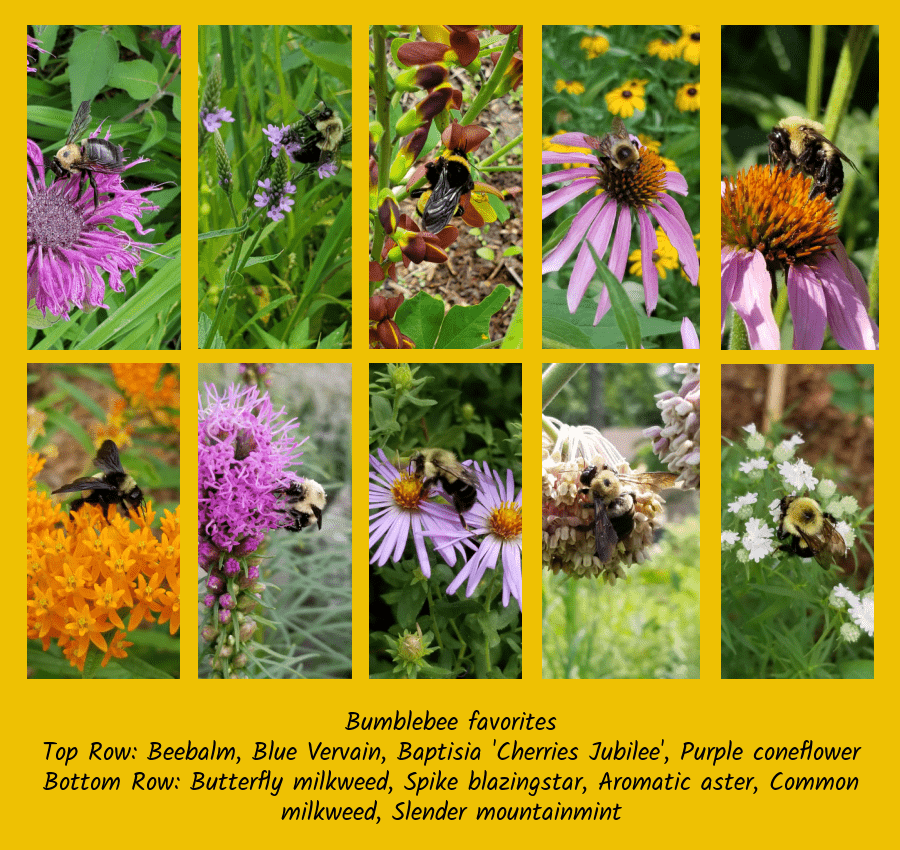

And finally, what do bumblebees really like? Going over the photos and observations I have from previous seasons; I see that they like a lot of things. The following lists include some of the more frequented plants that bumblebees alight on, in their different times of the year.

- April – Cutleaf toothwort, Bloodroot, Dandelion

- May – American linden, Virginia waterleaf, Baptisia, chives, Hardy geranium, Spider milkweed, American bladdernut

- June – Common milkweed, Baptisia, Slender Mountain mint, Spike blazingstar, coneflowers, catmint, comfrey, beebalm, agastache, Maltese cross, penstemon, butterfly milkweed, hollyhock

- July – Coneflowers, prairie clovers, grey-head coneflower, Prairie blazingstar, Rattlesnake master, agastache, hollyhock, catmint

- August – Ornamental onion ‘Millenium’, blue sage, tall sedum, blue vervain, swamp milkweed, catmint

- September – Goldenrods, obedient plant, blue sage, hairy aster, New England aster, wingstem, Seven son tree, catmint

- October – Aromatic Aster, gentians, catmint

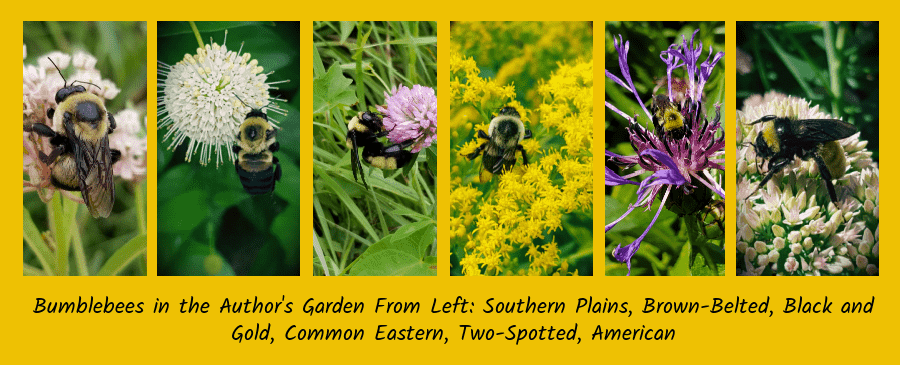

In my garden, there are 6 common bumblebees which frequent my flowers. These include the following:

In North America, there are 46 species of bumblebees, 2 of which as endangered as mentioned above. And 15 total recorded species in Kansas. Other ways to help bumblebees thrive in your gardens is to include brush piles on the edges, where they can make their nests. I once found a hive in an old rifle box behind my chicken house! Brush piles are great for other things besides bees, including Carolina wrens, snakes, spiders, and small mammals. All of these are part of the ecosystem of our landscapes, and we need to encourage them.

Conclusion

Bumblebees, just like our other 4000 native bees, are an important part of our ecosystems, and need to be encouraged in gardens and landscaping. I prefer to go the route of extreme biodiversity to attract them and other insects to my gardens. By increasing diversity to have at least 65% native over nonnative species, and by having more then 100 genera of plants, we can attain a landscape which have bumblebees not only present, but thriving.

Happy planting!