Welcome to the new year! Last season was one of the busiest gardening seasons for many across the country, with many new gardeners. With all those new gardeners, came a plethora of questions about a wide range of gardening topics. I am going to kick off the new year with one of the most important of those, pollinators.

Before I dive into the ways you can attract more pollinators to your garden, we need to discuss the different pollinators you might find. There are several groups of pollinators. These include insects, mammals, birds, and even spiders. We are going to focus on insect pollinators for this post.

What are the different insect pollinators?

When it comes to pollination, most people think about honeybees. But these are not the most efficient pollinators in North America, because they are not found naturally here. The bees, moths, butterflies, and other pollinators native to North America have adapted to the plants here.

Different kinds of insect pollinators include bees, wasps, moths, butterflies, flies, beetles, sawflies, and bugs. I am going to go over the main ones for gardeners, which are bees, wasps, flies, moths, and butterflies.

Bees as Pollinators

Here in the United States, we have around 4000 native bees, of which 90% are solitary. Most people, when they think of bees, they are thinking of the introduced honeybee. We are not trying to develop our landscape for honeybees, but for the native bees. But, honeybees will benefit from this work.

Bees are good pollinators of many types of flowers. Many of them are specialized, meaning they only pollinate a certain group of plants and are very good at it. Squash bees are one type of specialized bee. They forage and pollinate only on squash blossoms. The female bee makes a nest in the ground below the squash plant and the male bee sleeps in the blossom.

Types of Bees

There are many different types of bees found in across the country. Some are specialists and some are generalists. There are solitary bees and social bees. The main types that you will see in your landscape in the Central Great Plains to the Midwest are as follows.

- Mining Bees – about 1200 species. They make burrows in the soil.

- Sweat Bees – 500 species, mostly solitary, but some semi-social.

- Leafcutter Bees – 140 species. These cut leaves of many plants to make their nests in wood tunnels or soil.

- Bumblebees – Our only native truly social bees, they pollinate a wide variety of plants

- Digger bees – 217 species. They nest in the ground. Many are specialist of certain types of plants.

How to Attract Bees to the Garden

The best ways to attract and keep bees in the garden is to make places for them to build their nests, and provide native plantings. Instead of using mulch everywhere, plant a pollinator plot or meadow garden where there is no mulch between plants. This will provide open soil for many native bees.

You can also provide nesting spots by leave dead-standing tree, nurse trees, or brush piles in or around the garden. Many different types of bees will use these as homes for their brood.

Wasps as Pollinators

Wasps are not considered the best pollinators, because they do not have pollen sacs used for carrying pollen to their nests. Most of the larger wasp species I have observed in my own gardens and in the wild, eat spiders or caterpillars. They inject a paralyzing compound into their victim, then carry it to the nest. From here, they lay an egg next to the spider or caterpillar, which feeds on it after hatching.

Other wasps that do some pollination are parasitoid wasps, which are on the flower to gather nectar for food, before laying their eggs in their hosts.

Types of Wasps in the Garden

If you spend as much time as I do patrolling the garden for insects, you will observe the following wasps species visiting flowers for nectar. They do some pollination, but it is really quite minimal.

- Paper wasps – these social wasps build large nests under eaves or in bushes. Many people are allergic to their stings and do not want them near by.

- Potter and Mason Wasps – these are solitary wasps that build individual nest cells out of clay or mud. If you have ever broken into one of these nests, you likely have found a paralyzed caterpillar or spider next to a single egg.

- Parasitoid wasps – these do little pollination, but do feed on nectar before laying eggs in a caterpillar host.

Flies as Pollinators

When most people think of flies, they think about house and fruit flies, which are pests in the house. But many of the flies in the garden pull double duty as pollinators and beneficials, by eating pests. All the flies are considered to be efficient pollinators and should be encouraged in the garden.

Syrphid and Hover Flies

These are the most commonly seen flies in the garden. Because many of them often mimic bees and wasps, people often get them confused. The adult flies eat both pollen and nectar and fly regularly from flower to flower on the same plant. Larvae of these flies are mostly predacious, hunting and eating soft-bodied insects such as aphids.

Tachinid Flies

These flies generally eat only nectar when visiting flowers, but do provide pollination services. Their larvae feed on mostly on caterpillars. However, the swift feather-legged fly is a parasitoid of squash bugs.

Moths as Pollinators

Many of us only see moths when they come flying around the porch light at night. But did you know that they are out flying because they see the colors of flowers differently at night? I love moths and spend a lot of time researching and photographing them.

Moths, like butterflies, are not considered very good pollinators, because they have a long proboscis for sucking up nectar and may not need to actually land on the flower.

Butterflies as Pollinators

If you are not thinking about honeybees when you hear the word pollinator, then you are likely thinking about butterflies. Although most are quite showy, they are not very good at pollination. But, it is their value to the ecosystem that makes them an important part of our garden.

What plants are needed to attract pollinators?

Now that you have met some of the participants in our gardens, aka the insects, you need to know what plants and cultural practices to start on to attract more of them. The biggest emphasis in the garden should be on providing good nectar and pollen sources for the pollinators, which is best provided through biodiversity.

There are 2 sections to focus on when trying to attract more pollinators to the garden; native plantings and host plants. We will discuss native plants first.

Attracting pollinators through native plant biodiversity

To achieve a proper amount of biodiversity in your garden and landscape, you should focus on a mixture of plants that includes at least 60% native trees, shrubs, perennials, and grasses. The first thing you should do is to analyze your landscape and do a survey of the plants you already have. I mentioned how to do this in the blog about attracting birds.

Once you have your survey and know what plants you have and the percentage of native to nonnative, you can prepare to add more natives in as necessary. I reviewed the photos of pollinators I have taken over the last 4 years, and came up with a list of native perennials that the majority of pollinators visited.

- Asters

- Sunflowers

- Alliums (wild onions)

- Coneflowers (Echinacea species)

- Milkweeds

- Joe Pye Weeds (Eupatorium species)

- Mints

- Rudbeckias

- Eryngium species

- Salvias

- Baptisia

- Blazingstars (Liatris species)

- Verbenas

- Goldenrods

- Dogbane (Cynanchum laeve)

How to add these and other flowers to your landscape?

For many, adding new flowers into the landscape is something you are already used to. But it can be difficult when many of the native perennials are floppy or aggressive when not planted in a garden that mimics their native habitat. But you can add a pollinator plot or meadow garden to almost any landscape. A 10 ft by 10 ft space is all you need.

Creating a Meadow Garden

A meadow garden is a grouping of plants that use each other for support, share nutrients with root systems, and grow in similar sunny conditions. There should be a mixture of grasses, perennials, and some annuals in your meadow garden. It can be as small as 10 ft by 10 ft, or as large as you have room for.

Any of the above mentioned pollinator favorites can be added into your meadow garden. Also add some of the following plants.

GRASSES

Adding grasses not only to your meadow garden, but to the landscape in other areas will increase your diversity of pollinators. Many of the skipper butterflies use native grasses as host plants for their caterpillars, and I have seen small bees gathering pollen from grasses.

- Big bluestem

- Little bluestem

- Indiangrass

- Switchgrass

- Blue Grama

- Prairie Dropseed

- Gamagrass

- Wild Ryes

- Prairie Cordgrass

- Sideoats Grama

- Silver Bluestem

- Three-awns

SEDGES

Those who do not know yet about sedges, need to get in the game. Sedges are grass-like plants that grow in a wide variety of habitats. There are sedges for the forest, the field, and the wetlands. For your meadow garden use the following sedges.

- Leavenworth’s Sedge

- Texas Sedge

- Mead’s Sedge

- Fox Sedge

- Bottlebrush Sedge

- Woodland Sedge

PERENNIAL WILDFLOWERS

Add in these perennial wildflowers to attract specialized pollinators and to fill in gaps between blooming periods.

- Tall and Wavyleaf Thistles

- Beebalm

- Poppy Mallow

- Rose Mallow

- Culver’s Root

- Yellow Coneflower (Ratibida species)

- Compassplant

- Cup plant

- Wingstem

- Lobelia

- False Dragonhead

- False Sunflower

- Coreopsis

- Fall Phlox

- Prairie Phlox

- Golden Alexanders

- Penstemon

ANNUALS

Annuals from the native prairies and meadows of the Great Plains and Midwest should be included in the meadow garden. Many are season extenders which bloom for months.

- Annual Fleabane (Erigeron species)

- Bitter Sneezeweed

- Hairy ruellia

- Venus Looking-Glass (Triodanis species)

- Indian Blanketflower

- Rocky Mountain Bee Plant

- Clammy Weed

- Fragrant Cudweed

- Clasping Coneflower (Rudbeckia amplexicaulis)

- Annual Sunflower

Other ways to add natives to the landscape for pollinators

If you already have a well-planned landscape with permanent beds and just want to incorporate more natives, there are plants you can add in to replace existing nonnative. The following is a list of native perennials and nativars that work well in cultured landscapes, without floppiness.

- Coneflower – Sombrero Series

- Purple Milkweed

- Butterfly Milkweed

- Ironweed – ‘Iron Butterfly’

- Aster – ‘Raydon’s Favorite’

- Baptisia – ‘Purple Smoke’, PrairieBlues Series, Decadence Series

- Blazingstar – ‘Kobold’

- Rose Verbena

- Slender Mountain Mint

- Virginia Mountain Mint

- Fall Phlox – ‘Jeana’

- False Sunflower – ‘Burning Hearts’

- Rudbeckia – ‘American Gold Rush’

- Goldenrod – ‘Fireworks’

- Willowleaf Sunflower – ‘First Light’

- Little Bluestem – ‘Standing Ovation‘, ‘Carousel’

- Switchgrass – ‘Shenandoah’, ‘Northwind’, ‘Cheyenne Sky’

- Big Bluestem – ‘Blackhawks’

- Blue Grama – ‘Blonde Ambition’

- Bottlebrush Sedge

- Wild Geranium

- Big Blue Lobelia

- Gentian – ‘True Blue’

Designing your landscape with pollinators in mind by using native trees and shrubs

If you are working with a blank slate, or redesigning your outdated landscape, you will want to add as many native trees and shrubs into the plan. These are long-term plants, meaning that they will be in the landscape for more than 10 years. Most perennials, except long-lived perennials, will die out in less than 10 years.

Ask your landscape designer to use some of the following native trees and shrubs in the plan. These attract pollinators with nectar or are host plants for moths and butterflies.

Small Trees – Less than 30 ft tall

- Redbud – ‘The Rising Sun’

- Sourwood

- Red Chokeberry – ‘Brilliantissima’

- American Bladdernut

- Dwarf Chinkapin Oak

- Sassafras

- Flowering Dogwood

- Prairie Crabapple

- Eastern Hophornbeam

Medium Trees – 30 to 70 ft tall

- Osage Orange – ‘Whiteshield’

- Sugarberry

- Soapberry

- Black Willow

- Black Locust

- Blackjack Oak

- Sugar Maple – ‘Oregon Trail’

- Persimmon

- Pawpaw

Large Trees – 70 ft and taller

- Eastern Cottonwood

- Bitternut Hickory

- Pecan

- Chinkapin Oak

- Black Oak

- White Oak

- Bur Oak

- Red Oak

- Kentucky Coffeetree – ‘Espresso’

- American Sycamore

- Hackberry

- American Elm – ‘Prairie Expedition’, ‘Princeton’

- Black Walnut

Shrubs

- Atlantic Ninebark

- Silky Dogwood

- Prickly-Ash

- Eastern Wahoo

- Blackhaw Viburnum

- Rusty Blackhaw Viburnum

- Possumhaw Holly

- Winterberry Holly

- Buttonbush – ‘Sugar Shack’

- Western Sandcherry

- American Hazelnut

- Clove Currant

- Coralberry

- Snowberry

- Spicebush

How do we attract pollinators with host plants?

Host plants are plants that are used by butterflies and moths as food for their larval aka caterpillar stages. Nearly all native trees, shrubs, grasses, and perennials are used by some insect as a larval host. By adding in some of the best species of these plants, we can attract more pollinators to the garden.

I am going to list my top 21 pollinator host plants for gardens, and the number of lepidoptera (aka butterflies and moths) they support. This is a 2-part importance to the garden and ecosystem. Lepidoptera caterpillars metamorphize into active adult pollinators. But some caterpillar get eaten by other pollinators as well as by birds, mammals, and amphibians, making it better for the whole.

Top 21 Pollinator Host Plants

Herbaceous Perennials & Grasses

- Milkweeds – These support more than jus Monarchs. They are also host plants for cycnia moths and the milkweed tussock moth, as well as several other insects.

- Blue False Indigo – this is one of my favorite perennials. I have several cultivars. They are hosts for the wild indigo duskywing, various skippers, and the genista broom moth.

- Switchgrass – I have several cultivars as well as the straight species in my garden. They host various grass skippers and several moths including the Virginia ctenucha moth.

- Goldenrod – What is a garden without this plant? Boring. Besides being a pollinator powerhouse, it hosts moths such as the banded woolly-bear, hooded owlet, and wavy lined emerald.

- Prairie Violet – If you want fritillaries, make sure to have some violets in your garden.

- Purple Coneflower – Coneflowers are host to various checkerspot butterflies, the pearl crescent, and the wavy lined emerald moth, among others.

- Little Bluestem – This short grass is a favorite in landscaping. It is also a host for various grass skippers and the Virginia ctenucha moth.

- Field Pussytoes – If you want a low-growing groundcover for butterflies, look no further. This tiny plant supports both the painted lady and American lady butterfly.

- Wild Senna – Look no further for a host for sulphurs, yellows, and oranges.

- New England Aster – I love asters! They are hosts for crescents, silvery checkerspots, and the American lady butterfly. Also, they host moths such as the banded woolly-bear, the saddleback, the asteroid, and the goldenrod hooded owlet.

- Raccoon Grape – This vine hosts the beautiful wood nymph moth, as well as the achemon sphinx moth.

Trees & Shrubs

- Black Oak – Oaks host 534 species of lepidoptera including the banded hairstreak, Horace’s duskywing, and Juvenal’s duskywing butterflies. It also hosts many moths including luna, cecropia, polyphemus, spiny oakworm, unicorn, reversed haploa, waved sphinx, and the saddleback.

- Black Willow – Willows support a variety of moths and butterflies including the mourning cloak, viceroy, red-spotted admiral, Eastern tiger swallowtail, Io moth, luna moth, giant leopard moth, and more.

- Black Cherry – Together, members of the Prunus genus (cherries and plums) host 456 species of lepidoptera. These include the Eastern tiger swallowtail, coral hairstreak, red-spotted admiral, wild cherry sphinx, Imperial moth, luna moth, Io moth, and more.

- Hackberry – Hackberries host lots of butterflies including emperors, mourning cloaks, the Question mark, commas, and the American snout. And lots of moths too!

- Prickly-Ash – This little known small tree or shrub is a woodland understory plant. It hosts the giant swallowtail and is reported to also host the spicebush swallowtail.

- Diervilla – Bush-honeysuckle or diervilla hosts the snowberry and hummingbird clearwing moths, as well as other moths.

- Nannyberry Viburnum – Native viburnums host azures, Henry’s elfin, and the hummingbird clearwing moth.

- Bitternut Hickory – Hickories are hosts to 200 lepidoptera species. Species include hairstreak butterflies, the regal moth, the royal walnut moth, the luna moth, the hag moth, and the polyphemus moth, among others.

- Buttonbush – This large shrub hosts the hydrangea sphinx moth, cecropia moth, and the smeared dagger moth.

- Hazelnut – Not only do you get delicious nuts, you get a plant that hosts 161 species of lepidoptera. Including the white-marked tussock moth.

Other Practices to Help Attract Pollinators

I have gone over many of the various insect pollinators, plants to attract them, and host plants for moths and butterflies. But what other things can we gardeners do to attract pollinators to the landscape?

Things that we can do to attract a wider assortment of pollinators includes increasing bed size and decreasing lawn, use less mulch, eliminate dependence on chemical sprays, move fall cleanup to spring, and leave habitat spaces.

Reducing the Lawn

I know, this is the mower’s worst nightmare, when the customer says they are cutting back on how much lawn they have. I get it-I love the cool green grass feel between my toes. A well-manicured lawn breaks the movement and becomes a resting spot for the eyes. But lawns are typically dead zones for insects.

However, we can reduce our lawns to more useable sizes, while maxing out bed size for pollinators. Nothing upsets me more than a lawn that is not used for anything than a green looking space. If you are maintaining lawn, use it. Use it for recreation or sports.

I recommend to all my new and old customers that landscape beds be a minimum of 6 feet wide, preferably 9 feet wide or more. This will give you much more room for the plantings that usually out-grow their spaces and need constant trimming. I prefer to let shrubs, trees, and other plantings grow naturally, with little to no involvement from me or my pruners.

Use Less Mulch?

What did he say? Yes, I said use less mulch. When planting a meadow garden or pollinator plot, what good is it to keep the best pollinators away? Mining bees, leafcutter bees, and many bumblebees use the ground as a place for their nests, so what good does covering the soil do?

I still recommend and use mulch when it is important. Walkways, highly visible areas along the house or driveway, or areas with runoff problems. But one of the best mulches is native leaf litter. Insects and fungi break this down naturally, and there is usually room for bees too.

The problem with our wood mulches is that they have small open spaces and often lock tight together, doing the opposite of what we want them to do.

Eliminate Dependence on Chemicals

Americans have become obsessed with using chemicals. We spray for anything that looks out of place in the garden. We spray weeds in the lawn, we spray the bugs eating our tomato plants. But what effect do all these chemicals have on our native insect populations?

Many of chemical insecticides we spray are generalist killers, meaning that they kill everything. If we spray at the wrong time of day, we kill everything, both good and bad. And because populations of bad insects (aphids, scale, spider mites) grow more quickly than predators, we often kill off the predators leaving nothing to fight back against the bad insects. Except more chemicals.

The biggest reason why chemicals have become a problem is because Americans want everything to look pristine. We want our gardens as immaculate as the lawn. Well, if everything is whole and unchewed by any insect, then we will not have pollinators or birds either.

We need to accept the damage from native insects to our plants. And we need to learn to identify the native insect from the nonnative ones. Also, it would best to learn what insects may need a chemical control because of the lack of native predators. Keep learning fellow gardeners!

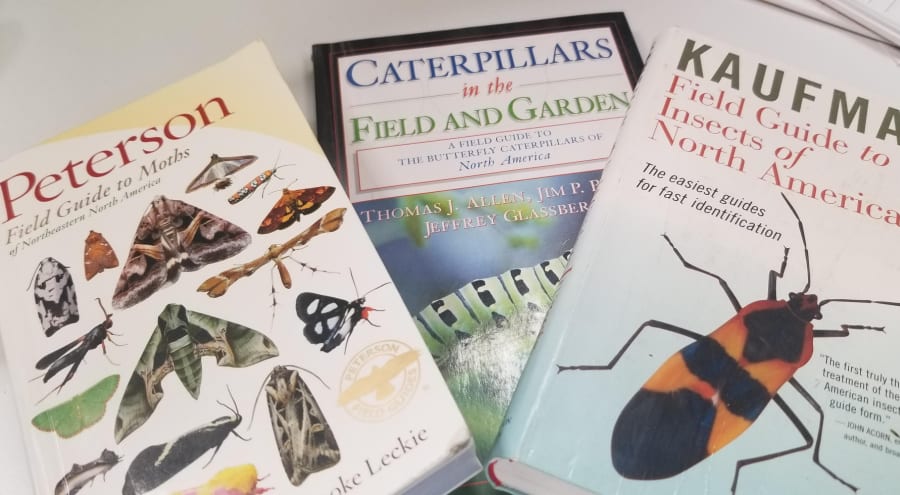

Identification Books for Insects and Diseases

The following list of books (and 1 website) can help you learn about insects and diseases. Once you begin to learn about these, you will know which ones may need a chemical application. READ ALL chemical labels before applying anything.

- Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America

- Peterson Field Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America

- Caterpillars in the Field and Garden by Allen, Brock, & Glassberg

- Good Garden Bugs by Mary Gardiner

- Pests of Landscape Trees and Shrubs printed by the University of California

- A Colour Atlas of Tomato Diseases by Blancard

- Tree and Shrub Problems in Kansas printed by Kansas State University

Move Fall Cleanup to Spring

Many of you have been reading over the last few years about gardeners who want you to leave the leaves, so to speak. I agree, in most cases that it is better to leave fall cleanup for spring. This gives overwintering insects a chance to hide among the leaves and litter, or in hollow stems for as long as possible.

That being said, in my own garden I leave as much of the fall cleanup until spring as possible. And when I do start spring cleanup, I cut back my perennials and natives and transfer the clippings to a brush pile or compost area.

Spring cleanup usually means burning for me. I like to burn off the native and nonnative grasses, as well as the meadow garden areas. I do not use mulch anymore in these areas, so the fire goes through quickly. This mimics the native habitat of the Great Plains prairie.

Habitat Spaces

I briefly mentioned these earlier in the post with regard to attracting native bees. If you have native woodland or prairie habitats near you, do your best to keep these pristine and clean. In your wooded areas, keep the invasives out (tartarian honeysuckle, Japanese honeysuckle, callery pear).

Let nurse or standing-dead trees stay where they are, unless they pose a risk to the house or animals. If you have to fall dead trees, let them lie on the ground as nurse trees.

Leave or build brush piles in various areas around the perimeter of the garden. These are homes to a variety of insects, plus birds, snakes, and other animals. And yes, snakes are good for the garden too.

Conclusion

Attracting pollinators to garden may seem like a rather daunting task after reading this post, but really, it can be very simple. Add native plants, reduce lawn and chemical dependence, maintain habitat, have fun!

Happy planting!